Confident, seductive, mysterious. Perfume has always offered more than scent. It awakens something within us, offering a shift in presence. Sociologist Georg Simmel described perfume as a kind of emotional costume, a tool for styling a personal aura that allows one to be sensed before being seen. Perfume became the most intimate yet accessible entry point into luxury. With a single spray, transformation begins. A dream becomes tangible because it lives on your skin. By the late 20th century, advertisers began crafting entire narratives around this emotional experience. Brands sold not just a fragrance, but a mood.

These fantasies did not exist in a vacuum; they mirrored the social and cultural desires of their time. Advertisers had to navigate shifting norms, especially around gender, while projecting futures and feelings just out of reach. It is no coincidence that this exploration began in the 1980s. During the time when research into emotion made significant strides. A new field called emotionology began to study emotion as a cultural and social construct. Researchers asked how emotions reflect the customs of a people and the values of their institutions. At the same time, the New York–based Fragrance Foundation published a booklet in 1984 titled The Forgotten Nose, highlighting the deep connection between emotion and scent. Advertising began to reflect these developments, portraying not just the fragrance itself, but the emotional response it could evoke. Let’s see how perfume ads from the 1970s to the early 2000s visualized emotion, — and how those emotional images revealed the anxieties, aspirations, and aesthetics of their cultural moment.

Yves Saint Laurent, Rive Gauche, 1979

By the late 1970s, the sexual revolution of the previous decade had left its mark on perfume advertising. Fashion was also evolving. Power dressing became a visual cue for women's growing autonomy and ambition. Suits with padded broad shoulders came to represent access to professional spaces that had long been reserved for men. As gender roles shifted, the emotional range women could express in public began to expand. Strength, desire, and independence were no longer off-limits. Yves Saint Laurent’s 1979 Rive Gauche campaign captured this moment. A woman, dressed in a white suit, drives a white convertible into an open horizon. The soundtrack, She’s Having a Lot of Fun Getting Married plays, but there is no groom. There is no need for one. From morning to night, from dusk to dawn, she belongs entirely to herself. This is a vision of femininity reimagined: not through the soft allure of patience and gentle lines, but through the speed and freedom of movement. At the same time, the perfume’s minimalist, cylindrical bottle carries a form that’s undeniably masculine. The power of her sexuality, her confidence, is ultimately framed through a design language that evokes the masculine, as if the only space for her power is in something borrowed.

Chanel, Fragrance № 5, 1979

Around the same time, Ridley Scott directed a Chanel No. 5 campaign that centered on a similar experience of female self-sufficiency, but explored a different emotional register. The ad shows a woman alone at the edge of a vast swimming pool. She undresses, reclines, and is completely at ease. A plane appears overhead. A man materializes, dives into the water, and swims toward her — only to vanish into thin air. She doesn’t react. Unbothered, she continues lounging, untouched by the spectacle. This is not about seduction or romance, but solitude as luxury. By presenting a woman who doesn’t perform desire and remains entirely self-contained, the ad subtly repositions Chanel No. 5 as a perfume not meant to attract others, but to affirm the self. It reinforces the brand’s mythology: a timeless, independent femininity. This is a kind of detached eroticism, where desire turns inward rather than outward. A woman, the ad suggests, is most alluring when she’s absorbed in herself — when she becomes her own object of fascination. Her refusal to respond to the fantasy unfolding around her doesn’t signal absence, but control.

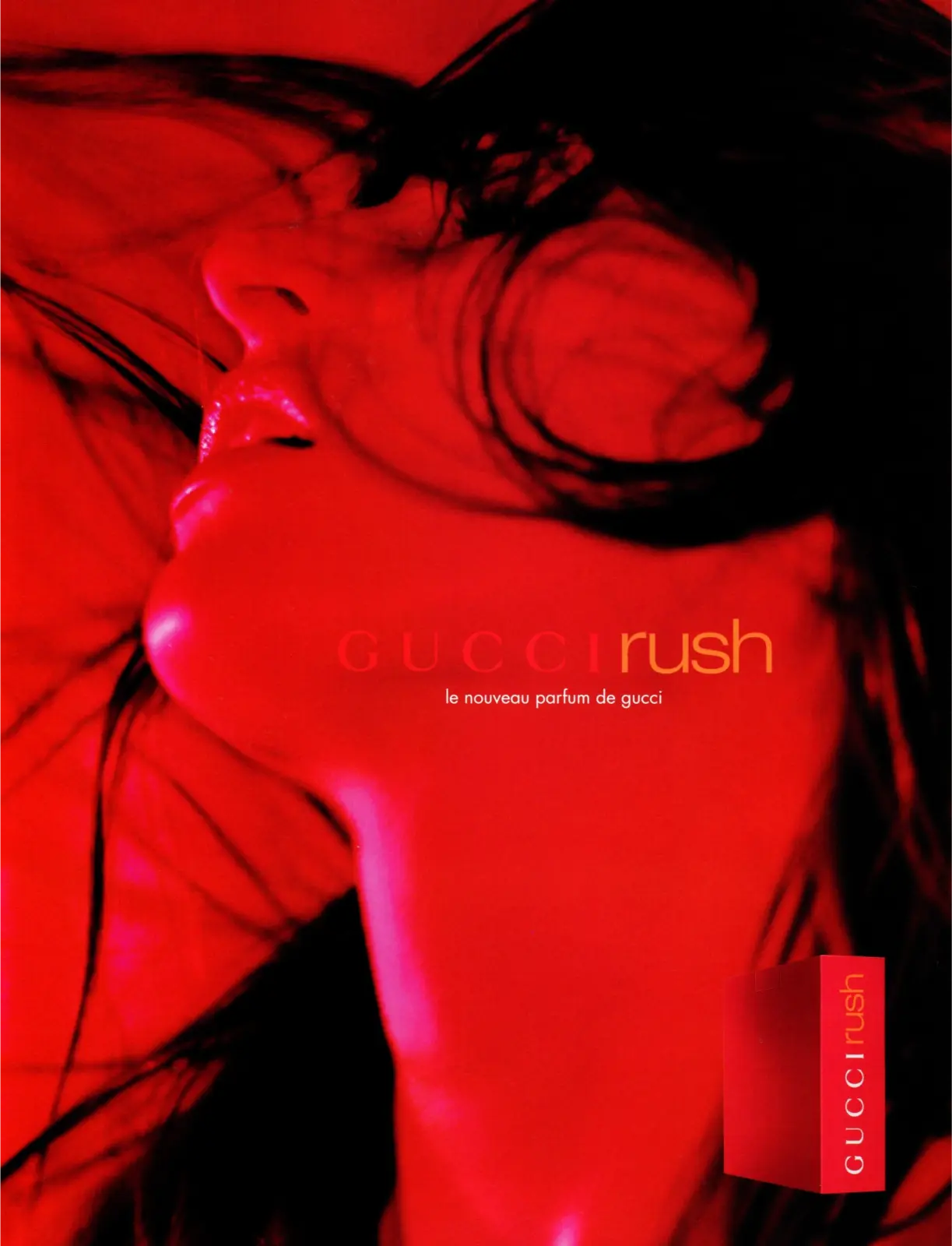

Gucci’s, Rush, 1999

In the 1990s, youth culture increasingly turned to escapism not as political withdrawal, but as a form of liberation. Club culture became a utopian space where music, drugs, and dance offered temporary relief from social pressures. On the rave floor, identities blurred. People of all genders and backgrounds found a shared sense of freedom in collective euphoria. For many young women, this subculture offered something especially radical: pleasure outside the male gaze. This emotional climate was captured in the 1999 Gucci Rush commercial. Against a fast-cut montage of clouds, city lights, ocean waves, and surreal interiors, a woman floats through an urban dreamscape. There’s no clear narrative, no love interest — only motion, sensation, and the feeling of intoxication. The ad doesn’t present the perfume as a tool of seduction, but as a portal to a heightened emotional state. The woman’s erotic relationship isn’t with a partner but with the product itself. She becomes part of a sensory loop: image, sound, speed, scent. In this way, Rush captures the 1990s ideal of emotional intensity as self-contained and synthetic. The perfume becomes a vehicle for fantasy, a way of feeling more deeply and more quickly. Emotion here isn’t quiet or internal; it’s pulsing, neon, and commodified ecstasy.

Emporio Armani, He/She perfume, late 1990s

Emporio Armani’s Get Together campaign captures a turning point in how intimacy was visualised at the end of the 20th century. In the ad, a man and a woman exchange text messages from within a sleek, high-tech interior — a setting that evokes the sterile sensuality of Björk’s All Is Full of Love music video (1997). Single words flash across the screen: “together,” “love,” “touch.” There’s no dialogue, no perfume bottle in sight. The message is emotional, mediated, and abstract. At the end, the couple finally meets and shares a kiss, and this moment feels both intimate and distant, filtered through the coolness of their surroundings. What’s striking is how desire is represented not as seduction, but as mutual recognition. The ad promotes two fragrances — one for him, one for her — and frames the encounter as a balanced exchange. Both characters reach for each other. Both are the object and the subject of desire. This subtle equality marks a break from earlier narratives, where perfume was primarily marketed to women as a tool for attracting men.

Advertising doesn’t mirror reality. But it does shape cultural fantasy. Around the same time, sociologist Eva Illouz published Consuming the Romantic Utopia (1997), in which she argued that love had been reshaped by capitalism into a consumer experience. Since the early 20th century, beauty products have been sold with the promise of romantic success and emotional fulfillment. What Illouz identified was the commodification of emotion — love as something you could buy. Get Together reflects this logic, but with a twist: perfume doesn’t guarantee love, it becomes a language through which emotional equivalence is performed. In this world, fragrance isn’t about enchantment or conquest. It’s about connection. Mediated, technologized, but equal.

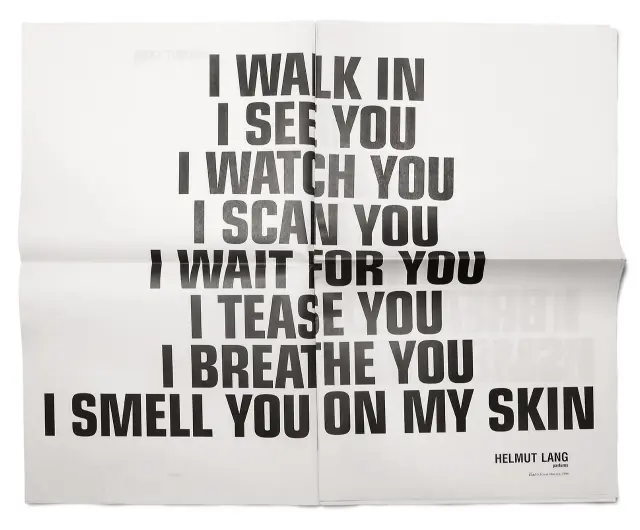

Helmut Lang, Parfums and Eau de Cologne, 1999-2000

The preceding narrative is strikingly reminiscent of the Helmut Lang Parfums campaign, which eschewed traditional imagery of eroticism in favor of something far more cerebral. While most perfume ads relied heavily on theatrics and sensuality, Lang took a radically different approach. The idea for the Helmut Lang fragrance stemmed from a collaboration with artist Jenny Holzer for the 1996 Florence Biennale. Holzer, known for projecting intimate, often confessional text onto urban surfaces, helped shape Lang’s vision. Phrases like “I breathe you” and “I feel you on my skin” became the conceptual centre of the perfume. When it came time to launch it, Lang once again turned to Holzer, giving her complete creative control over the campaign.

The campaign featured only Holzer’s words, rendered in stark, minimalist text. This rejection of emotional storytelling reflected a broader cultural shift in the late 1990s, as global economic and humanitarian crises shifted attention from spectacle to raw reality. Scent was no longer an elixir for fantasy; In Lang’s vision, it became embedded in a more utilitarian, even clinical, world. In the accompanying video ad, Lang focused on the process of perfume distillation, an unflinching look at the machinery and production behind the product. Lang’s minimalistic aesthetic revealed the back-end of perfume production: laboratory glassware resembling factory chimneys, mechanics over magic. In doing so, Lang echoed his deconstructive approach to fashion, which stood in stark contrast to the commercial opulence of the industry at large. By exposing the cold apparatus of desire, Lang inverted the Barthesian script: instead of humanizing advertising, he mechanized it. Perfume became not a dream, but a system.

By the early 21st century, emotion had become the currency of luxury perfume marketing. Advertisers were no longer simply selling desire; they were manufacturing it, translating cultural moods into affective imagery. Creators of perfume campaigns had to capture the spirit of the times, align with industrial and social progress, and simultaneously offer visions of fantasy. These visions needed to be aspirational enough to entice, yet familiar enough not to alienate. Perfume advertising reveals how gender roles, aesthetic ideals, and emotional norms have been continually imagined, shaped, and commodified. Increasingly, these campaigns feature images of emancipated women but the underlying message remains that liberation, confidence, and even selfhood itself are attainable through scent. Perfume becomes the conduit through which transformation is promised. Ultimately, these campaigns serve as emotional archives: repositories of feelings both remembered and imagined.

-

, Writer